When it was first announced in 1995 that the beloved Irish poet Seamus Heaney had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, Heaney was in rural Greece and could not be reached, not even by family members. What is it about Greece and Ireland? Of course the two are bound together in ancient ways by their shared Indo-European linguistic and mythological heritage. But it’s the pull of the two cultures on poets and scholars in modern times that is the theme of my thoughts today. I recently had a chance to visit the west coast of Ireland for a seventh time. I never feel more at home than when I am there, though I was 25 years old the first time I went.

Today’s very long post unites two subjects that have long been dear to me: the so-called Homeric Question and the Blasket Islands, which are located just over a mile off the Dingle Peninsula on the west coast of Ireland. I am a Classicist by training and my research and publications have to do with the poetics of the Iliad and Odyssey as orally composed traditional poems. Back in the 90s in graduate school, I had the good fortune to know the scholar of Greek laments Margaret Alexiou, and it was she who introduced me to the literature of the Blasket Islands in Ireland. Her father was the Classicist George Thomson, whose visits to the Blasket Islands in the early 20th century will be a focus of this post. I have since visited the Great Blasket (and the Blasket Centre on the mainland) a number of times, and I have enjoyed reading the published tales of the islanders that have been translated into English, but until relatively recently I had never united my Irish interests with my Homeric ones.

This photo shows a view of the Great Blasket from Dunmore Head. We will come back to this place. But first, we need to go quickly to Athens.

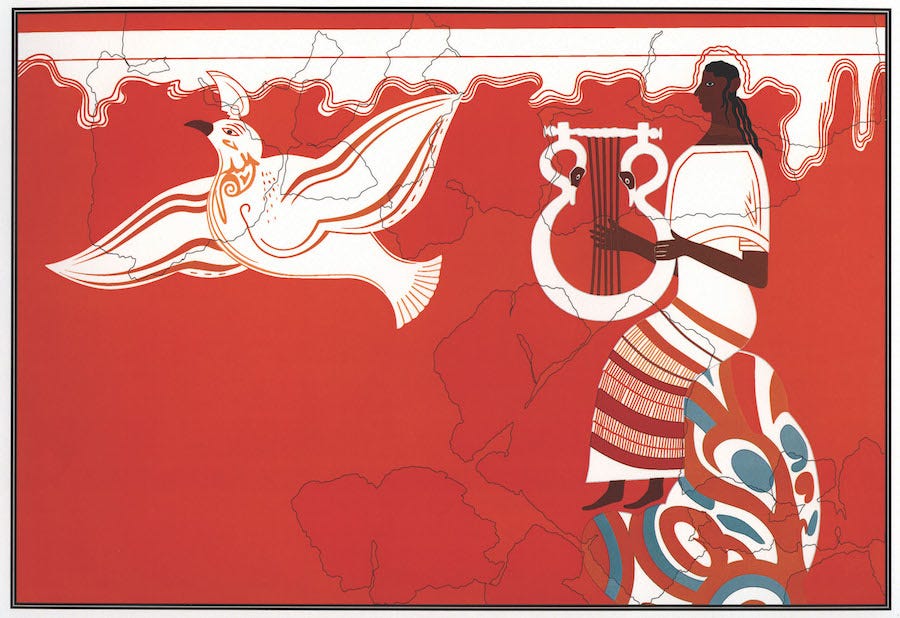

In the 6th century BCE, Athens was ruled by the tyrant Peisistratus and he is cited by several much later ancient sources as the organizer of a so-called Peisistratean recension. This recension, it is claimed, produced, in the sixth century BCE, the first written and authoritative text of the Homeric epics, the Iliad and Odyssey. Five hundred years later the Roman orator Cicero writes in his work On Oratory [3.137] that Peisistratos was supposedly so learned and eloquent that [quote] “he is said to be the first person ever to arrange the books of Homer, previously scattered about, in the order that we have today.” Now, before we take this story too literally and think we have solved the “Homeric Question”—that thousands of years old question (which is, in reality, many questions) as to how and when and by whom the Iliad and Odyssey came to be composed and written down—we should note that the Peisistratus story has a close affinity with tales in other cultures about how an oral tradition came to be authoritatively fixed in writing (for the following see also Nagy 1996b:70–75). Let me relay to you a story about the Irish epic, The Cattle Raid of Cooley:

The poets of Ireland one day were gathered around Senchán Torpéist, to see if they could recall the Táin Bó Cuailnge in its entirety. [Senchán Torpeist was the Chief Poet of Connacht circa 640 CE.] But they all said they knew only parts of it. Senchán asked which of his pupils, in return for his blessing, would travel to the land of Letha to learn the version of the Táin that a certain sage took eastward with him in exchange for the book of Cuilmenn. Emine, Ninéne’s grandson, set out for the east with Senchán’s son Muirgen. It happened that the grave of Fergus mac Roich was on their way. [note: Fergus is one of the kings of the Ulster Cycle of Irish myth, and a character in the Táin.] They came upon the gravestone at Enloch in Connacht. Muirgen sat down at Fergus’s gravestone, and the other’s left him for a while and went looking for a house for the night.

Muirgen chanted a poem to the gravestone as though it were Fergus himself. He said to it:

‘If this your royal rock

were your own self mac Roich

halted here with sages

searching for a roof

Cuailnge [i.e. The Cattle Raid of Cooley] we’d recover

plain and perfect Fergus.’

A great mist suddenly formed around him - for the space of three days and nights he could not be found. And the figure of Fergus approached him in fierce majesty, with a head of brown hair, in a green cloak and a red-embroidered hooded tunic, with gold-hilted sword and bronze blunt sandals. Fergus recited him the whole Táin, how everything had happened, from start to finish. Then they went back to Senchán with their story, and he rejoiced over it. (Táin Bó Cuailnge, translation by Thomas Kinsella)

Lest you think that story is just a one off, here’s another: according to Ferdowsi’s Shâhnâma, that is, the Persian Book of Kings, [I 21.126-136], a noble vizier once assembled the wise men who are experts in the Law of Zoroaster, from all over the Empire, and each of these brought with him a fragment of a long-lost book of the Book of Kings that had been scattered to the winds. Each of the experts was then called upon to recite, in turn, his respective fragment, and the vizier composed a book out of these recitations. In this story the vizier reassembles the old book that had been disassembled, which in turn becomes the model for the Shâhnâma or “Book of Kings” of Ferdowsi (Shâhnâma I 21.156-161).

So, probably Peisistratos did not actually assemble a definitive text of the Iliad and Odyssey. Instead, his very important role in promoting the performance of poetry at the Athenian festival of the Panathenaia is later remembered this way, as a way of explaining, retroactively, how a vast oral tradition became a relatively fixed text. As we have just seen, similar aetiological stories survive from a number of different oral poetic traditions.

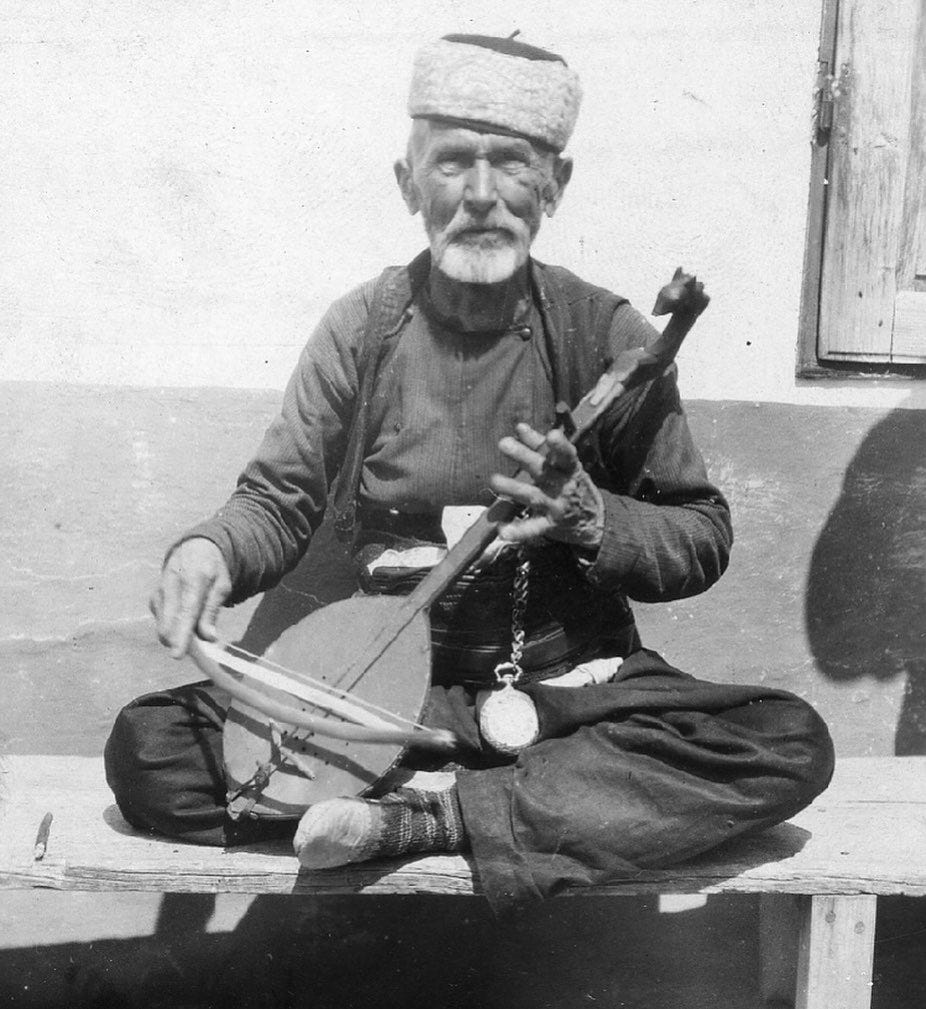

Now let’s jump ahead 2500 years. In the early 1930s, the young Harvard scholar Milman Parry undertook fieldwork in the country that was then Yugoslavia, in order to observe the workings of a living oral epic tradition. He would go on to apply that fieldwork by analogy to the Homeric epics, and suggest that the Iliad and Odyssey were composed orally and in performance, by means of a traditional diction and a process similar to that which he had observed in the South Slavic epic tradition. The singers in this tradition did not memorize their poems nor did they improvise exactly either. Rather they drew upon a storehouse of traditional tales and themes and characters and made use of a formulaic diction that had evolved for centuries precisely to enable singers, who had been trained in the techniques of their fathers and grandfathers, to compose heroic songs before an audience on any given occasion. They did this to the accompaniment of a musical instrument known as the gusle. Milman Parry died tragically young at the age of 33 in 1935, but already by that time his work had set the stage for a revolution in our understanding of the composition and transmission of the Homeric Iliad and Odyssey.

Prior to undertaking this fieldwork, Parry had exhaustively demonstrated in two theses submitted to the Sorbonne in 1928 that the diction in which the Homeric epics were composed was highly traditional, consisting of formulaic phrases that fit within the dactylic hexameter, which is the meter of the poems. He also showed that two formulaic phrases meaning the same thing rarely, if ever, occupied the same metrical space within a verse. To cite just one example, there are thirteen different ways to address the hero Achilles in the Iliad, but no two of those phrases has the same metrical shape. Parry understood that such a highly stylized body of formulaic language, one that was so, as he called it, “economical,” could not have been the work of one man. But when he wrote and defended his Paris theses, he had not yet made the leap into orality. As he later wrote:

My first studies were on the style of the Homeric poems and led me to understand that so highly formulaic a style could be only traditional. I failed, however, at the time to understand as fully as I should have that a style such as that of Homer must not only be traditional but also must be oral. It was largely due to the remarks of my teacher (M.) Antoine Meillet that I came to see, dimly at first, that a true understanding of the Homeric poems could only come with a full understanding of the nature of oral poetry. It happened that a week or so before I defended my theses for the doctorate at the Sorbonne, Professor Mathias Murko of the University of Prague delivered in Paris the series of conferences which later appeared as his book La Poésie populaire épique en Yougoslavie au début du XXe siècle. I had seen the poster for these lectures but at the time I saw in them no great meaning for myself. However, Professor Murko, doubtless due to some remark of (M.) Meillet, was present at my soutenance and at that time M. Meillet as a member of my jury pointed out with his usual ease and clarity this failing in my two books. It was the writings of Professor Murko more than those of any other which in the following years led me to the study of oral poetry in itself and to the heroic poems of the South Slavs. (The Making of Homeric Verse, 439)

It was only when Parry went to Yugoslavia to observe the still flourishing South Slavic oral epic song tradition that he came to understand that Homeric poetry was not only traditional, but oral—that is, composed anew every time in performance, by means of a sophisticated system of traditional phraseology and diction. For Parry, witnessing the workings of a living oral epic song tradition was a paradigm shift. Suddenly, by analogy with the South Slavic tradition, the workings of the Homeric system of composition became clear to him.

Scholars before Parry had proposed that the Iliad and Odyssey were composed orally, but never before had the system by which such poetry could be composed been demonstrated, nor were the implications of the creative process truly explored. Parry’s early death prevented him from undertaking this work, and it would fall to his young assistant at the time, Albert Lord, to conduct further fieldwork and lay out the many implications of what they had observed. Lord would go on to become Professor of Slavic and Comparative Literature at Harvard. By the time he went into retirement, he was a member of three departments: Slavic Studies, Classics, and Comparative Literature. He was also the founder of Harvard’s degree in Folklore and Mythology. And he was the first Curator of the Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature. He published, among many other things, the enormously influential book, The Singer of Tales, the culmination of decades of close observation of a living oral epic tradition in Yugoslavia and careful application of that work by analogy to the Homeric epics.

The importance of the work of Parry and Lord cannot be overstated. Though of course many have built upon and refined their arguments, and some others try very hard to avoid grappling with the implications, few would contest their central assertions about the nature of Homeric epic, with the result that Homeric scholarship must be divided between that which came before and after the paradigm shift that they initiated. And yet, as we have already seen, Parry did not emerge from a vacuum. Others were already laying the groundwork that would lead him to Yugoslavia. For the rest of this essay I want to look back to the intellectual world of the decade just before Parry and Lord’s first trip to Yugoslavia, when a scholar named George Thomson found Homer, so to speak, in Ireland.

Before I get there, let me just note here that Parry’s 1928 major thesis, written prior to his fieldwork, began with the following quote from a work of Ernest Renan that was published in 1890:

Comment saisir la physionomie et l’originalité des littératures primitives, si on ne pénètre la vie morale et intime de la nation, si on ne se place au point même de l’humanité qu’elle occupa, afin de voir et de sentir comme elle, si on ne la regarde vivre, ou plûtot si on ne vit un instant avec elle?

How can we grasp the physiognomy and the originality of primitive literatures, if we do not penetrate the moral and intimate life of the nation, if we do not place ourselves at the very point of humanity that it occupied, in order to see and feel like it does, if we don’t observe it living, or rather if we don’t live with that nation for a moment?

Years before he embarked upon his collecting trip to Yugoslavia, Parry was imagining himself as an anthropologist, describing the literature of a “primitive” people whose way of life he had come to know. Perhaps not uncoincidentally, in the two decades prior to Parry submitting that thesis, students and scholars of various sorts had been doing just that, immersing themselves in the culture of the Great Blasket island, a remote community off the west coast of Ireland, where Irish had never ceased to be spoken, and a traditional, subsistence way of life persisted into the twentieth century.

The students and scholars who came to the Blaskets at the beginning of the twentieth century were not looking to find Homer, or at least not consciously. Early visitors included the folklorist Jeremiah Curtin, botanists, priests, and missionaries. In the initial years after the founding of the Gaelic League in Ireland and eventually the establishment of the school of Irish Learning in Dublin, most came to the Blaskets in search of a pure form of spoken Irish, uncorrupted by English or the modern world. It was for precisely this reason that the playwright John Millington Synge, who had previously spent a great deal of time on the Aran islands, visited the Great Blasket in 1905. (The Aran Islands are, like the Blaskets, located off the West coast of Ireland and a relatively isolated, Irish-speaking community resided there at that time.) The poet William Butler Yeats, who had spent time there himself, had urged Synge to go there and “Live as if you were one of the people themselves.”

See photos: JM Synge’s snapshot of life on Blasket (From The Irish Independent)

In the years after Synge came to the Great Blasket, a Norwegian linguist named Carl Marstrander, an Assistant Keeper of Manuscripts at the British Museum named Robin Flower, and a wealthy young Irishman in search of a vocation and a knowledge of Irish, Brian Kelly, spent extended periods of time on the Great Blasket island over many years and formed life-long relationships with the inhabitants. These men all interacted with and were taught Irish by a particular inhabitant of the Great Blasket, Tomás Ó Criomthain, who spoke some English and was literate in Irish, and had lived on the island since his birth in 1856. He had already lived nearly half a century when Synge visited in 1905, and had experienced island life in all its hardship and vicissitudes of fortune. With Brian Kelly’s encouragement and assistance Ó Criomthain would eventually publish in both Irish and English two volumes of his stories and reflections on his long life, Island Cross-Talk and The Islandman (which was first translated by Robin Flower), among several other volumes in Irish. Ó Criomthain was the first and most famous, but many islanders would go on to publish their own memoirs and stories, including Peig Sayers, one of whose books became a standard one in the Irish school curriculum.

Blasket authors (From the Blasket Centre)

One of these early visitors to the Blaskets in search of Irish was Marie-Louise Sjoestedt, a young French linguist (of Swedish descent) who became one of the Blasket’s most consistent visitors in the 1920’s and ’30’s (Kanigel 2012:119–128). She had studied Slavic languages among many others, but was eventually guided toward Celtic Studies by Professor Antonie Meillet—the same Meillet who had pointed Milman Parry in the direction of orality and who, along with Matthias Murko, had encouraged Parry to go to Yugoslavia. Sjoestedt would go on to receive a lectureship at Trinity College Dublin and then from there she would immerse herself in West Kerry Irish and the Blaskets.

These visitors were all looking for Irish, and yet it is worth noting that just prior to visiting the Aran Islands, Synge had taken a year-long course at the Sorbonne taught by Celtic scholar Henri D’Arbois de Jubainville (1827–1910), entitled “The civilization of Ireland compared with that of Homer” (Martin 2007:79). Synge’s subsequent prose account of the Aran Islands (entitled simply The Aran Islands), though it never explicitly mentions Homer, is infused with imagery and attention to details of daily life that would captivate the interest of those who were familiar with the poetry of the Homeric epics. It’s not inconceivable that Synge believed that he had found the world of Homer in the Aran Islands.

Paul Henry (1876-1958), Launching the Currach (1910-1911), in the National Gallery of Ireland

Not long after Synge and in those same years as Marie-Louise Sjoestedt, beginning in 1923 when he was just 20 years old, the Classics scholar George Derwent Thomson became enthralled with the Blaskets. His first visit was just one year after the creation of an independent Irish state. Thomson’s parents were supporters of Irish independence and in his teens he had been proccupieded with the Easter Rising of 1916. He joined the Gaelic League, and began studying Irish at its London branch. In 1922 he won a scholarship to study Classics at King’s College, Cambridge, where he earned rare double firsts in the Classical Tripos. But his first summer as a student at King’s was spent not immersed in the study of the Classical world, but rather on the Great Blasket, and many summers thereafter. Thomson won a fellowship, moreover, which allowed him to spend the academic year 1926-1927 at Trinity College Dublin, and he later left his prestigious position at King’s in order to become a lecturer and then Professor of Greek at University College Galway, where he taught Classical Greek literature in Irish. At the time few Classical texts were available in Irish, but George Thomson translated them, including the Odyssey, his recent completion of which had secured him the position in Galway. He later published editions in Irish of both Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound and Euripides’ Alcestis as well as three of Plato’s dialogues. Thomson left Ireland in 1934, however. He was frustrated that his radical ideas about bringing Classical learning to the common man in Irish were being met with bureaucratic opposition. He returned to King’s College in 1934 to lecture in Greek, and then became Chair of Greek at Birmingham University in 1936 where he remained until he retired in 1970.

What did this eminent scholar of Greek seek in the Blasket Islands? Many have made connections between Thomson’s communist politics and Marxist scholarship, taken up in later years, and his time spent in the Blaskets. But initially, it seems, he was simply a young man who wanted to learn Irish. The story that both George Thomson and the famed Blasket author Maurice O’Sullivan [Muiris Ó Súilleabháin] tell is that they met moments after George arrived on the Great Blasket at the age of twenty in 1923, whereupon they had a conversation in a mixture of English and Irish, George’s Irish still being rudimentary at that time. They immediately hit it off and became fast friends. George naturally fit in with the young people of the island, socializing, attending dances, and forming many relationships in the fundamentally communal life of the Blaskets. But he and Maurice were the closest, and it is thanks to Maurice that George’s spoken Irish became so fluent. After several summers on the island, George convinced Maurice not to emigrate to America, as most young people on the island at that time were doing or contemplating doing, but to join the civic guard in Dublin. When Maurice became bored in that profession (he was posted to a remote place in Connemara, without many crimes to attend to, apparently), George encouraged him to write down his life story and memories of island life, much as Brian Kelly had done with Tomás Ó Criomthain. After several years of close collaboration, Twenty Years A Growing was published in both Irish and English. George Thomson was the translator of the English edition, together with Moya Llewelyn Davies, with whom both Maurice and George were close. Also close with this literary and intellectual group was the novelist E. M. Forster, who wrote in the preface to Twenty Years A Growing, “here is the egg of a sea-bird—lovely, perfect, and laid this very morning.”

What does Forster mean by the “egg of a sea-bird”? Well, on the one hand, Forster explains the metaphor for us. Like a sea-bird, Forster says, Twenty Years A Growing is “lovely, perfect, and laid this very morning.” But _why_ is it those things? Just before offering that metaphor Forster writes: “He [that is, the reader] is about to read an account of neolithic civilization from the inside. Synge and others have described it from the outside, and very sympathetically, but I know of no other instance where it has itself become vocal, and addressed modernity…” There is a lot to unpack in that statement. But it seems Forster is suggesting that what is exciting about this work is that it allows the modern reader to hear the living voice of someone on the inside of a prehistoric civilization. That voice has created something perfect and lovely and brand new, but what he has created is at the same time very old, in that it reflects a way of life that is ancient, much as sea-birds have been laying eggs since the dawn of time. Each egg is lovely and new, but the biological system that created that egg is ancient. That is what I take from it at least.

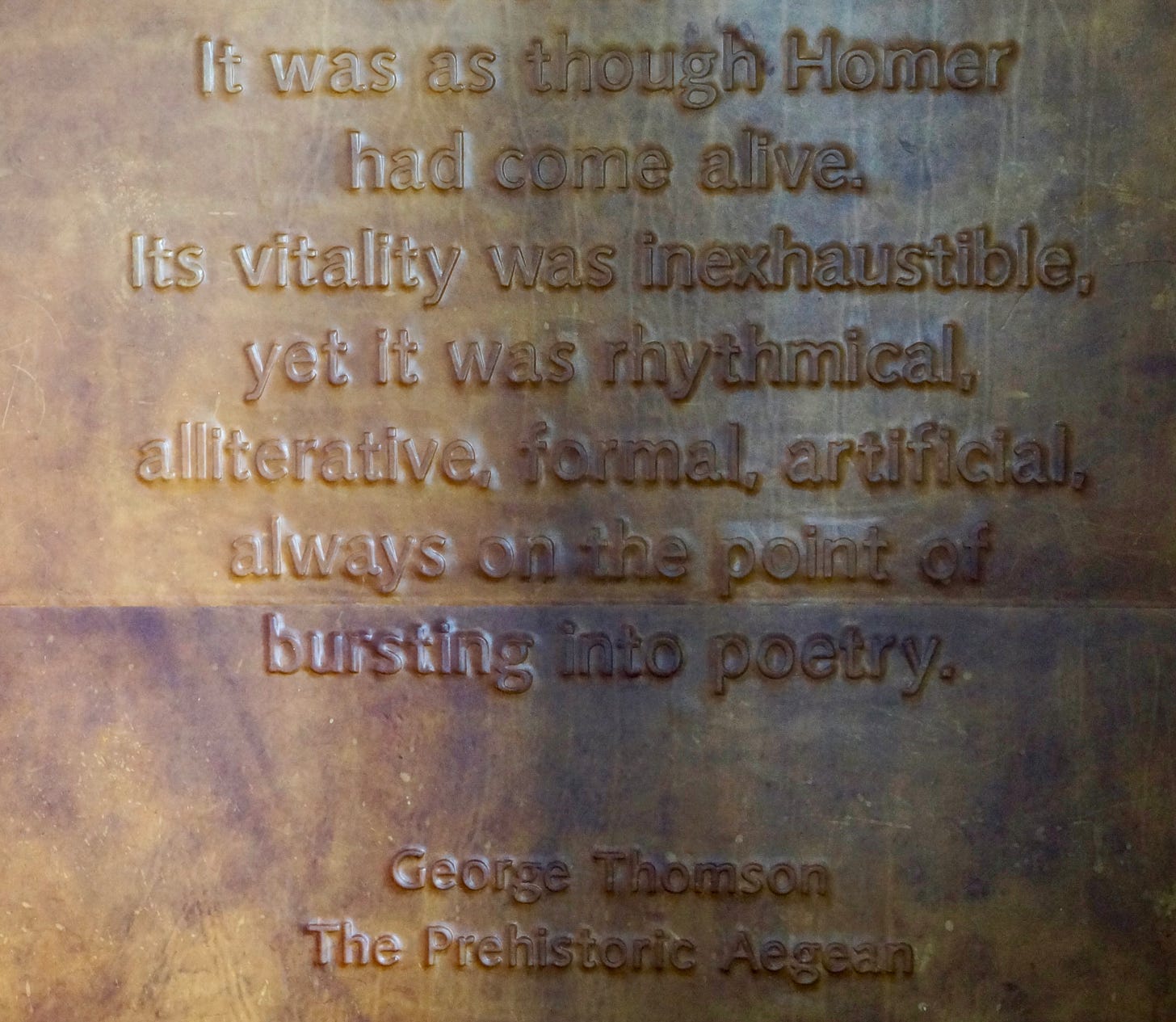

Forster, like Synge, conjures Homer without ever mentioning his name, with his metaphor that sounds like a Homeric simile, and his invocation of a “neolithic civilization.” And indeed, for the modern reader, Twenty Years A Growing feels like an orally composed, spoken work, a kind of prose poetry. The first words of the book invite us into an almost magical world: “There’s no doubt but youth is a fine thing, though my own is not over yet, and wisdom comes with age.” George Thomson himself described the Irish language of the Blaskets this way: “Its vitality was inexhaustible, yet it was rhythmical, alliterative, formal, artificial, always on the point of bursting into poetry” (Thomson 1949:540).

Not only is the language of Twenty Years A Growing poetic and rhythmical (even in translation, thanks to Thomson), but it seems to depict a Homeric world—not the world of kings and battles, but the peaceful, natural world of the Homeric similes, or the city at peace on the shield of Achilles, with its singing and dancing, harvest, and wedding—though as Thomson himself notes, certainly the people of the Blaskets had more than their fair share of hardship, poverty, and grief. Twenty Years A Growing was a literary sensation, and since its English edition came out the year before the English edition of Ó Criomthain’s Islandman, it was the book that introduced the culture of the Blaskets to a modern, English-speaking world.

The desire to recover a purer form of Irish in the far west, in the far more rural part of Ireland, was inspired in part by nationalist interests, but that is not the whole story—many of the early visitors to the Blaskets were not Irish. This longing for a culture that is cut off from and completely ignorant of modern life intersects with scholarship of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries which understood the Homeric epics to have been composed by a quote unquote “primitive” folk poet of “original genius” whose monumental epic poems were transmitted orally for centuries. As such, these epics were thought to embody the creativity of a primitive culture.

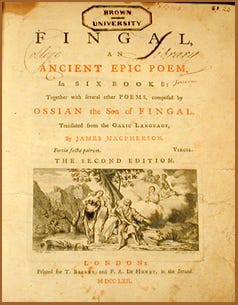

In the 1760s, James Macpherson, influenced by these ideas about Homer, surmised that a parallel process had occurred in Celtic lands, and identified the mythological figure of Ossian as the “Homer” of Gaelic poetry. [In 1760 Macpherson published his Fragments of Ancient Poetry Collected in the Highlands of Scotland, and Translated from the Gallic or Erse Language, followed by Fingal, An Ancient Epic in 1761 and Temora, An Epic Poem in 1763.] Macpherson attributed this body of poetry to a blind third century Gaelic warrior turned bard, Ossian who was the son of Fingal (aka Finn Mac Cumail in Irish myth). The “poems” (which were in fact rendered in rhythmic prose) were a huge success, enchanting England and Europe, and had a significant impact on subsequent literature, helping to usher in the Romantic Movement. For a brief time Ossian was more beloved than Homer. Oscar Wilde, whose full name is Oscar Fingal Wilde, was named for characters in Ossian (and they are also of course found in Irish legend, Oscar being the son of Ossian). Wilde’s mother wrote after he was born: “He is to be called Oscar Fingal Wilde. Is not that grand, misty, and Ossianic?” It was soon discovered that Macpherson’s “translations” of Highland epics were largely poems of his own creation, based loosely on the oral songs and tales and manuscripts that he had collected in trips to the Highlands in 1760 and 1761. In fact it seems that a desire to discover the truth about Macpheron’s sources contributed directly to the development of the academic field of Celtic languages in Europe (MacKillop 1986:2). But the fact that Macpherson’s works were embraced as fervently as they were speaks to how epic poetry was understood at the time.

Homer was able to compose works of genius, it was thought, because he lived in a primitive historical period most conducive to experiencing and observing the kinds of events that make up great poetry. In the eighteenth century it was being argued that every culture proceeds through the same stages of development, and that it is only in the earliest stages that poetic genius can flourish. This conception of epic poetry, established well before Macpherson began his series of “translations,” was so powerful that the composition of epic poetry had virtually ceased in Britain by the 1760s. Epic was understood to be the natural and spontaneous expression of the culture that produced it, in either the so-called “Savage” or “Barbarian” phase (Rubel 1978). In fact, as Rubel’s study documents, the works of Homer and Ossian came to be regarded as the quintessential examples of the Barbarian and Savage periods respectively in the history of societies. This tendency to interpret poetry as a witness to and product of the time period in which it was composed gained momentum after the publication of the Works of Ossian.

Well over a century later, the image of Homer as a primitive folk poet whose genius emerged from the natural world and the people all around him persisted. And in Ireland at that time there was a sense that just such a primitive, creative culture in the Irish-speaking West was on the verge of extinction. In his Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry the poet Yeats writes, “These folk-tales are full of simplicity and musical occurrences, for they are the literature of a class… who have steeped everything in the heart: to whom everything is a symbol.” And in The Celtic Twilight, with its blind wandering poet Raftery, Yeats writes: “these poor countrymen and countrywomen in their beliefs, and in their emotions, are many years nearer to that old Greek world, that set beauty beside the fountain of things, than are our men of learning.” A similar conceptualization of the relationship between a peasant life and the creativity of poetry pervades the work of John Millington Synge as well. It is a fundamentally Romantic worldview that has been harshly criticized modern times, as much for its inaccuracy as for the rosy picture it paints of a life that was in reality full of hard manual labor, the cruelty of the elements, lack of medical care, and at times, starvation. And yet, what I would like to suggest is that, flawed as it was, such a conception of the nature of poetry became a bridge to a more systematic understanding of the workings of oral literature.

It is worth quoting here in some depth both George Thomson’s and his predecessor Robin Flower’s reflections on how they were affected, as scholars, by their encounter with the Irish stories of the Blasket islanders. In his book The Prehistoric Aegean (which is of course, about Greek culture), Thomson writes about not understanding, in his youth, the formulaic diction of Homeric poetry, with its repeated phrases and verses. Then, he says, “I went to Ireland.”

“It was as though Homer had come alive. Its vitality was inexhaustible, yet it was rhythmical, alliterative, formal, artificial, always on the point of bursting into poetry… Returning to Homer, I read him in a new light. He was a people’s poet—aristocratic, no doubt, but living in an age in which class inequalities had not yet created a cultural cleavage between hut and and castle. His language was artificial, yet, strange to say, this artificiality was natural. It was the language of the people raised to a higher power. No wonder they were enraptured.” (George Thomson, The Prehistoric Aegean, p. 540)

Robin Flower, the keeper of Celtic manuscripts at the British Museum who began coming to the Blaskets 13 years before Thomson did, writes in a similar vein:

“Some years ago I was wandering idly one day along a road upon an island which lies three miles out into the Atlantic beyond the most westerly point of Ireland. The island is entirely Irish in speech, and the older inhabitants still preserve a rich treasure of song and story. As I strolled along I heard a call from the next field…

He had been digging potatoes in a furrow of the field, and he now laid the potato spade crosswise over the furrow and, sitting down on one end, courteously signed to me to take my place on the other end. I did so and, without further preamble or explanation, he fell to reciting Ossianic lays. For half an hour I sat there while the firm voice went steadily on. After a little while he changed from poetry to prose, and began to recite a long tale of Fionn and his companions and their adventures throughout the world, how they came to Greece and what strange things befell them there. At times the voice would alter and quicken, the eyes would brighten, as with a speed which you would have thought beyond the compass of human breath he delivered those highly artificial passages describing a fight or a putting to sea, full of strange words and alliterating rhetorical phrases which, from the traditional hurried manner of narration, are known as ‘runs’. At the end of one of these he would check a moment with triumph in his eye, draw a deep breath, and embark once more on the level course of his recitation. I listened spellbound and, as I listened, it came to me suddenly that there on the last inhabited piece of European land, looking out to the Atlantic horizon, I was hearing the oldest living tradition in the British Isles. So far as the record goes this matter in one form or another is older than the Anglo-Saxon Beowulf, and yet it lives still upon the lips of the peasantry, a real and vivid experience, while, except to a few painful scholars, Beowulf has long passed out of memory. Tomorrow this too will be dead, and the world will be the poorer when this last shade of that which once was great has passed away.

The voice ceased, and I awoke out of my reverie as the old man said: ‘I have kept you from your dinner with my tales of the fiana.’ ‘You have done well,’ I said, ‘for a tale is better than food’, and thanked him before we went our several ways. (Flower, The Irish Tradition, pp. 104–106)

Thomson and Flower both seem to feel that they have witnessed the last days of a vibrant oral traditional culture, whose epic tales of Finn and the Fiana, and whose natural poetry and everyday storytelling continue to imbue spoken Irish with vibrancy and poetry. Flower does not make an explicit comparison to Homer, as Thomson does, but his mention of Beowulf and “Ossianic lays” reveals that he is thinking of an Irish oral epic tradition along the lines of a Homeric one. Both imply that it is the ancient and uncorrupted culture of the Blaskets that allows such poetry to still live, and that when the culture vanishes, so too will the poetry.

So natural was the affinity between the Blasket culture and the world of Homer, that much as with Macpherson and Ossian, once again the one began to influence the other, at least in George Thomson’s mind. Plans were made for Maurice O’Sullivan to edit Thomson’s Odyssey translation “to give it an authentic Blasket Island flavour” (Ó Lúing 1996:156). This manuscript was sadly lost when Thomson moved from Galway back to King’s and to my knowledge it has never been recovered. But it seems clear that Thomson felt not only that the Odyssey should be accessible to native speakers of Irish in the Gaeltecht, but also that that there was an important connection to be made between Blasket life and the language of the Odyssey. And indeed Thomson makes the affinity explicit in a chapter—entitled “Fuit Ilium” (which in Latin means something like “Troy existed but does no more”)— of his book on the Blasket islands, an expanded edition of which was published the year after Thomson’s death. He writes: “The island of Ithaca had little to offer besides mountain pasture — ‘It is a rough place,’ says Odysseus, ‘but a fine nurse of men’” (Thomson 1988:71).

The scholar Seán Ó Lúing, who met Thomson at the end of his life and discussed with him his Blasket experiences, notes that in the Irish version of Thomson’s Blasket memoir (which was published in 1977) he stated: “It’s in Blasket that I found the key to the Homeric Question” (“Sa Bhlascaod a fuaireas an eochair don gCeist Hóiméarach”). What did he discover there? Thomson puts it this way in The Prehistoric Aegean (1949:577, 581–582):

Who then is Homer? He is not a compilation… Nor is he a solitary miracle. The unitarians do not want to explain Homer, but to envelop him in the magic of individuality and the miracle of genius. But, though his songs have never been surpassed, they are not a miracle. Homer is not one but many hereditary poets, gifted and practised, who, together with the enthusiastic crowds that spurred them to excel themselves and the far-sighted statesman that saved their masterpieces for posterity, may be described in Shelley’s words as both creations and creators of their age…

All theories of authorship, single or composite, are beside the point. The concept of authorship is inapplicable. These poems took shape out of a kaleidoscope background of impromptu variations adjusted to the inspiration of the moment, crystallizing gradually as the power of improvisation failed. And they were brought to rest so gently that in their final configuration the simple realism and natural eloquence of primitive, popular poetry was combined with the subtle, self-critical individualism of mature art. That is their unique quality… And all of this was rendered possible by a unique combination of historical circumstances which laid a bridge between improvisation and composition, between speech and writing, so that something of the unpremeditated audacity of the primitive minstrel, inspired by the shining eyes and breathless silence of the crowd, was carried over into the impassive but durable medium of the written word.

Thomson is thinking here at the end of ancient Greece and that Peisistratean Recension with which I began, and I have stated that the story is not likely a viable one. But his conceptualization of an oral tradition composed by generations of poets that gradually crystallizes is quite sophisticated, and it is a metaphor used by scholars of the Homeric tradition today. Thomson, moreover, is already in 1949 drawing on the work of Milman Parry, which Thomson quotes approvingly in the preceding pages. He was among the very first to do so. In 1949, the publication of Albert Lord’s paradigm shifting book The Singer of Tales was still 11 years away.

In 1930, three years before Milman Parry and Albert Lord began recording and transcribing the South Slavic epic singers, Robin Flower—that keeper of Celtic manuscripts at the British Museum—began recording the stories and songs of the Blasket Islanders on a machine called the Ediphone, which employed wax cylinders somewhat like the aluminum discs that Parry and Lord used or later vinyl records (Kanigel 2012:191).

Five years later, the Irish Folklore Commission began sending their own collectors. The Great Blasket (in reality a tiny place) became famous as an oral literary hub, and was swamped with visitors. A movie was even filmed there at this time, right around the same time that the far more famous Man of Aran was filmed. In the movie, a Dublin medical student comes to the Great Blasket and falls in love with a local girl, eventually leaving everything behind and becoming an “island man” (Kanigel 2012:244). As Robert Kanigel points out, technology in the 1930’s was both preserving and romanticizing a quickly vanishing culture while at the same time hastening its demise.

The same was true of Parry and Lord with their own recording equipment. Literacy and technology were infiltrating the system, such that by the 1950s, Albert Lord had a hard time finding traditional singers in Yugoslavia and Albania who were not making use of printed song books to learn their songs. Instead of composing lengthy songs in performance, with a great deal of interaction with the audience, who were all steeped in the tradition themselves, the professional singers, now literate in many cases, were memorizing songs that had been collected and printed. The tradition was dying out, and at least in part it was the collectors trying to preserve the tradition who were contributing to its demise. That’s the thing about oral literature. It only truly lives in a world in which it can’t be fixed in written form or recorded on physical objects. As George Thomson himself writes in The Prehistoric Aegean (Thomson 1949:575): “The peculiar beauty of epic diction, as compared with written poetry, is its fluency and freshness. That is the virtue of improvisation. It takes on new colours as it passes from one festive occasion to another, sparkles in response to momentary stimulus. But its lustre cannot be caught. Its words are winged and cannot be pinned down.”

One of the fascinating aspects of the Blasket example is the written dimension of the literary phenomenon that took place. For much of its history the Great Blasket had a school, and many of the islanders were literate in Irish and knew some English. People like Brian Kelly and George Thomson encouraged the islanders to write down their own life stories and the traditional tales that they knew, but the writing down did not always come easily—not for want of literacy, but because of the fundamental disconnect between the oral process and the literate one. Peig Sayers’s books were in fact dictated, not written down by the author herself, and so in that sense they remain orally composed works. It has been theorized that Maurice O’Sullivan’s Twenty Years a Growing was so successful because it was heavily edited by George Thomson both in Irish and in English. It is not clear how heavy his hand was but it seems he did have a great deal of influence on the final product (Kanigel 2012:163). O’Sullivan drafted another volume of memoirs about his adult life in Connemara (Twenty Years in Bloom), but the project was rejected by publishers and never came to fruition, nor did he ever compose the novel that Thomson proposed that he write. He continued to publish shorter stories and articles, but he never quite recaptured the vibrant dynamic that made Twenty Years A Growing so enthralling.

In Yugoslavia, Parry and Lord encountered similar obstacles in their attempts to put songs composed orally onto the printed page. The singers they observed in the 1930s were not literate, so their songs had to be recorded with audio equipment or transcribed by hand. But some singers could not slow down enough to dictate their songs, or perform them without the accompaniment of the gusle. Even though Albert Lord himself had famously theorized that the Homeric Iliad and Odyssey were the products of a dictation process, near the end of his life, in a footnote to his 1991 collection of essays, Epic Singers and Oral Tradition, he wrote the following (Lord 1991:47–48):

As I reconsidered very recently the stylization of a passage from Salih Ugljanin’s “Song of Bagdad” that was found in a dictated version but not in two sung texts, I was suddenly aware of the experience of listening to Salih dictate… One might think that dictating gave Salih the leisure to plan his words and their placing in the line, that the parallelism was due to his careful thinking out of the structure. First of all, however, dictating is not a leisurely process… I might add that not all singers can dictate successfully. As I have said elsewhere, some singers can never be happy without the gusle accompaniment to set the rhythm of the singing performance.

Lord died in the same year that this book was published. He never had the chance to follow up on this realization, or consider what it meant for the Homeric Question.

The Blaskets were inhabited until 1953, when the final 22 residents were evacuated by the Irish government. With no modern services, plumbing, or electricity, no easily accessible school at that time or hospital, the islands were deemed unfit for life. So it is true that Robin Flower and George Thomson and the island’s many other visitors in the 1920s and 30s were witnessing the end of something. But as late as the 1980s, researchers were connecting the dots between Homer and Western Ireland, and desperately trying to record the last traces of an oral literary tradition. Author and documentary filmmaker Michael Wood recorded a storyteller named John Henry for his 1985 documentary In Search of the Trojan War. Henry is portrayed as the last of his kind in Western Ireland. In the documentary, Michael Wood is explicitly seeking the answer to the Homeric Question, trying to find out and represent to viewers how a story like that told in the Iliad could be passed down for hundreds of years.

Such a clip helps to explain why Greek students and scholars, people like Robin Flower and George Thomson, have been drawn to the Blaskets. It is almost as if they are looking for the recipe for an oral tradition, the special conditions from which something like the Iliad or Odyssey might emerge. Already in the 1910s and 20s there were precious few examples of truly “oral” culture left to study. The Great Blasket was one of them, even though, as we have seen, even it was not an entirely “oral” place.

Author Robert Kanigel, whose 2012 book On an Irish Island chronicles much of the story I have told here, went on to write a biography of Milman Parry that came out in 2021. He went from a study of Blasket life and literature, with a focus on the scholar George Thomson, to a study of Parry’s contribution to the Homeric Question. Meanwhile I took the same journey in reverse. Soon after reading the work of Milman Parry for the first time, I became fascinated by the Blasket islands. My husband and I got engaged at the Cliffs of Moher on the west coast of County Clare in 1999, and we went to the Blaskets and the Aran Islands on that same trip. We named our first son Finn, after Fionn Mac Cumhaill. I was in graduate school at the time of that first trip to Ireland, studying Homer. What was I looking for there?

There is something about the Blasket Islands, like a Homeric simile, that seems somehow outside of time but also to connect us to our past, perhaps even to something eternal. Early visitors like Robin Flower and even Blasket islander Maurice O’Sullivan himself imagined this place in the furthest west of Ireland as the gateway to Tír na nÓg, the Land of the Young:

The sky was cloudless, the sea calm, sea-birds and land-birds singing sweetly. The sight of my eyes set me thinking. I looked west to the edge of the sky and I seemed to see clearly the Land of the Young — many-coloured flowers in the gardens; fine, bright houses sparkling in the sunshine; stately, comely-faced, fair-haired maidens walking through the meadows gathering flowers. Oh, isn’t it a pity Niamh of the Golden Hair would not come here now, thought I, for it is readily I would go with her across the top of the waves… It seemed to me now that the New Island [= America] was before me with its fine streets and great high houses, some of them so tall that they scratched the sky; gold and silver out on the ditches and nothing to do but to gather it. I see the boys and girls who were once my companions walking the street, laughing brightly and well contented. I see my brother Shaun and my sisters Maura and Eileen walking along with them and they talking together of me. The tears were rising in my eyes but I did not shed them. (O’Sullivan, Twenty Years A Growing)

As Kanigel writes of the legend, in which the hero Ossian experiences the land only to lose it, “The Land of the Young was one of perfect happiness, yes, but always beyond one’s reach, impossible to attain lastingly” (Kanigel 2012:96). So too does this communal world of the Blaskets, with its farming and fisherman’s way of life, with its dancing and storytelling and life in the outdoors, with its dare I say Homeric way of existence, not unlike the feasting Phaeacians of the Homeric Odyssey, who vanish without a trace before the story is over, seem both eternal and just out of reach. Perhaps we moderns just missed it; perhaps it was never really there. But a fascination with the possibility endures.

To wrap up this very long essay, let me just reiterate my goal for today, which has been to show that even before the work of Milman Parry in Yugoslavia, people were looking to Ireland to try to understand the origins of Homeric poetry and how to interpret it. Scholars interested in Ireland intuitively understood the traditionality of Homeric poetry, that it could not be the work of one man but was instead the culmination of many generations of poets and people, and that the culture was shaped by and steeped in this tradition, well before Parry and later Albert Lord articulated how this could be so in practical terms. This intuitive understanding seems to have arisen, at least in part, out of the long standing associations between so-called “primitive” literature and “original genius.” These Romantic associations, problematic as they are from a modern standpoint, nevertheless allowed Thomson to find his own answer to the Homeric Question in the Blasket Islands, and later to embrace the work of Milman Parry well before others did so.

Yeats told Synge to go to the Aran islands; Meillet told Marie-Louise Sjoestedt to go to the Blaskets. In the Blaskets, for Thomson, “It was as though Homer had come alive.” The poetry and story telling they found there can be heard no more but the reverberations can still be felt in Nobel-prize-winning poetry of Seamus Heaney, whose work was described in the New York Times when he won that prize this way: “In an almost literal sense, Mr. Heaney’s poetry is rooted in the Irish soil. He has often written of the poet as a kind of farmer, digging and rooting, as though Ireland’s wet peat were a storehouse of images and memories. At the same time, Mr. Heaney moves easily from the homely images of the farm and village to larger issues of history, language and national identity, creating what he once called “the music of what happens.”” If we hear Homer at all in Heaney, it is because that music is both ancient and composed just now, alive and infused with the oral poetic tradition that Heaney inherited from his ancestors.

Works cited

Agostini, R. 1996. “J. M. Synge’s ‘Celestial Peasants.’” In Genet 1996a:159–173.

Alexiou, M. 2000. “George Thomson: The Greek Dimension.” In Ní Chéilleachair 2000: 52–74.

Arbois de Jubainville, H. d’ 1899. La civilisation des Celts et celle de l’épopée homérique. Paris.

Blair, H. 1760. Preface. In Gaskill 1996:5–6.

–––. [1763] 1765. A Critical Dissertation on the Poems of Ossian. In Gaskill 1996:342–399.

–––. 1783. Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres. London.

Bynum, D. 1974. “Child’s Legacy Enlarged: Oral Literary Studies at Harvard Since 1856.” Harvard Library Bulletin 22: 237–267.

Child, F., ed. 1882–1898. The English and Scottish Popular Ballads. Boston.

Curtin, J. 1890. Myths and Folklore of Ireland. London.

Flower, R. 1944. The Western Island: The Great Blasket. Oxford.

–––. 1947. The Irish Tradition. Dublin.

Garcia, J. 2001. “Milman Parry and A. L. Kroeber: Americanist Anthropology and the Oral Homer.” Oral Tradition 16: 58–84.

Gaskill, H., ed. 1991. Ossian Revisited. Edinburgh.

–––, ed. 1996. The Poems of Ossian and Related Works. Edinburgh.

Gathercole, P. 2007. “Aeschylus, the Blaskets and Marxism: Interconnecting Influences on the Writings of George Thomson.” In Luce, Morris, and Souyoudzoglou-Haywood 2007: 43–54.

Genet, J., ed. 1996a. Rural Ireland, Real Ireland? Gerrards Cross, UK.

–––. 1996b. “Yeats and the Myth of Rural Ireland.” In Genet 1996a: 139–157.

Graziosi, B. and E. Greenwood, eds. 2007. Homer in the Twentieth Century: Between World Literature and the Western Canon. Oxford.

Kanigel, R. 2012. On an Irish Island. New York.

–––. 2021. Hearing Homer’s Song: The Brief Life and Big Idea of Milman Parry. New York.

Lord, A. B. 1953. “Homer’s Originality: Oral Dictated Texts.” Transactions of the American Philological Association 94:124–34.

–––. 1960/2000. The Singer of Tales. Cambridge, Mass. 2nd ed., ed. S. Mitchell and G. Nagy.

–––. 1991. Epic Singers and Oral Tradition. Ithaca, N.Y.

Luce, J. 1969. “Homeric Qualities in the Life and Literature of the Great Blasket Island.” Greece & Rome 16: 151–168.

Luce, J., C. Morris, and C. Souyoudzoglou-Haywood, eds. 2007. The Lure of Greece: Irish Involvement in Greek Culture, Literature, History and Politics. Dublin.

MacKillop, J. 1986. Fionn mac Cumhaill: Celtic Myth in English Literature. Syracuse.

Macpherson, J., ed. 1761. Fingal: an ancient epic poem, in six books: together with several other poems composed by Ossian the son of Fingal, translated from the Galic language, by James Macpherson. London.

–––. 1763. Temora, an ancient epic poem, in eight books; together with several other poems composed by Ossian, the son of Fingal, translated from the Galic language by James Macpherson. London.

–––. 1765. The works of Ossian, the son of Fingal, translated from the Galic language by James Macpherson. 3rd ed. London.

–––. 1773. The Iliad of Homer. London.

Martin, R. 2007. “Homer among the Irish: Yeats, Synge, Thomson.” In Graziosi and Greenwood 2007: 75–91.

Ní Chéilleachair, M., ed. 2000. Seoirse Mac Tomáis 1903–1987. Ceiliúradh an Bhlascaoid 4. Dublin.

Ó Crohan, T. 1929/1937. An t‑Oileánach. Translated by Robin Flower as The Islandman. Dublin.

Ó Lúing, S. 1980. “Seoirse Mac Tomáis-George Derwent Thomson.” Journal of the Kerry Archaeological and Historical Society 13: 149–172.

–––. 1996. “George Thomson.” Classics Ireland 3: https://web.archive.org/web/20130319083517/http://www.classicsireland.com/1996/oluing96.html.

O’Sullivan, M. 1933. Fiche Blian ag Fás. Translated by M. Davies and G. Thomson as Twenty Years A-Growing. Dublin/New York.

O’Toole, F. “An island lightly moored.” The Irish Times, edition of 29 March 1997.

Parry, A., ed. 1971. The Making of Homeric Verse: The Collected Papers of Milman Parry. Oxford.

Parry, M. 1928. L’épithète traditionelle dans Homère: essai sur un problème de style homérique. Paris. [Reprinted and translated in A. Parry 1971:1–190.]

Radlov, V., ed. 1866–1896. Proben der Volkslitteratur der türkischen Stämme und der Dsungarischen Steppe. St. Petersburg.

Renan, E. 1890. L’avenir de la science: pensées de 1848. Paris.

Rubel, M. 1978. Savage and Barbarian: Historical Atitudes in the Criticism of Homer and Ossian in Britain, 1760-1800. Amsterdam.

Seaford, R. 1997. “George Thomson and Ancient Greece.” Classics Ireland 4: 121–133.

Simonsuuri, K. 1979. Homer’s Original Genius: Eighteenth Century Notions of the Early Greek Epic (1688-1798). Cambridge.

Sjoestedt, M. 1949. Celtic Gods and Heroes. trans. M. Dillon. Methuen.

Stafford, F. 1988. The Sublime Savage: A Study of James Macpherson and the Poems of Ossian. Edinburgh.

Stanford, W. 1976. Ireland and the Classical Tradition. Dublin.

Synge, J. 1907. The Aran Islands. London.

–––. 1911. In Wicklow, West Kerry and Connemara. Dublin.

Thomson. G. 1929. Greek Lyric Metre. Cambridge.

–––. 1940. Aeschylus and Athens: A Study in the Social Origins of Drama. 2nd ed. 1945. New York.

–––. 1945. Marxism and Poetry. London.

–––. 1949. Studies in Ancient Greek Society: The Prehistoric Aegean. 2nd ed. 1954. London.

–––. 1977. An Blascaod a bhi. Maynooth.

–––. 1988. Island Home: The Blasket Heritage. Dingle.

Thanks so much for this lovely post. I had no idea of this deep-rooted connection between the Homeric and the Irish strands of oral poetry, but after reading your essay it feels almost self-evident, natural, ordained.

Small reference question: do you know of any work focused on the formal aspects of oral poetry, the formulas and structures mentioned recurrently in the text, in a variety of poetic traditions (or maybe just Homeric)? I expect this might not exist, or might require a great command of the actual language (whereas I speak neither Greek nor Irish).