This post is about a paper I published in 2006, originally developed as part of a conference I organized with Richard Armstrong in 2005 entitled The Homerizon: Conceptual Interrogations in Homeric Studies.

The origins of the paper lie in my dissatisfaction with the concept of invention in Homeric studies. “Invention” is the term used when we try to find the authorial genius behind the Iliad or Odyssey. If the Iliad and Odyssey were composed in a traditional, oral medium, we ask ourselves, what is Homer’s contribution? I feel that we are still severely limited by modern concepts of authorship when dealing with the Homeric poems. We just aren’t comfortable with a Homer who doesn’t consciously strive to “invent” anything, a Homer whose contribution is his skillful composition in performance using traditional techniques, a Homer who is not particularly different than any of the other skilled performers who came before or after him, a Homer who is one of many. I find it interesting that the concept of the inventing Homer is double edged. When something seems really good or poetically sophisticated, we often assign it to Homer. Oh that part about Patroklos, that’s good stuff. Homer invented that. (The implication being that a traditional medium could not produce something that good.) Likewise when something is really bad: well the whole thing about Niobe having to eat but being a stone, frankly, it’s awkward. The reason is because Homer invented it and couldn’t quite fit it in right. The paradox with a traditional system like the South Slavic one that Parry and Lord studied and, I believe, the system in which the Iliad and Odyssey were composed, is that innovation occurs without a doubt, but the singers composing within that system do not strive to innovate. They claim to reproduce the same song word for word every time, yet they never do. It is only the outsiders to the tradition who can come and observe that realize this. For those on the inside, the tradition remains constant. This is something that our culture does not easily relate to. Imagine Shakespeare not wanting to be innovative, or Monet, or Frank Lloyd Wright. The people we admire, the people we call geniuses, were innovators.

In the early 2000s I became intrigued intrigued by this question of invention as it applies to a very different body of work, namely James Macpherson’s purported translations of Scottish Highland epic in the eightteenth century. My fascination with Macpherson and began when I was asked to do a chapter for a “companion” volume to ancient epic, a chapter entitled “Homer’s Post-Classical Legacy.” Not an easy task for 6000 words, but I learned a lot and one of the things I learned was how incredibly influential, if only for a short time, Macpherson’s Ossianic poetry was on the art, literature, music, and culture of Europe (a major driving force towards the Romantic movement) and how intricately the whole Ossianic phenomenon was tied up in the Homeric scholarship of the day and the developing Homeric Question. For a brief time Ossian was more beloved than Homer. I love it that Oscar Wilde, whose full name is Oscar Fingal Wilde, was named for characters in Ossian (and they are also in Irish legend). Wilde’s mother wrote after he was born: “He is to be called Oscar Fingal Wilde. Is not that grand, misty, and Ossianic?”

All I knew initially was that Macpherson was considered a huge faker, his Ossianic poems forgeries, and that intellectuals obsessed with primitive genius had been gullibly taken in by him in their desire to find another testbed for their theories about the nature of genius. But when I read a little about Macpherson’s life (he was born and raised in the Highlands and members of his family were active resisters of the English control of the region), I realized that the situation was much more complicated than that. Because there were Highland storytelling, song, and poetry traditions, traditions that were cognate with the Irish ones. Macpherson, a native Gaelic speaker, grew up amidst those traditions, and in fact his neighbor was a well know story teller, Finlay Macpherson.[1] The characters in Macpherson’s Ossianic poems are traditional characters; Fingal is the Scottish equivalent of the Irish Finn Macool, after whom my own son Finn is named. And because myth is dynamic, not static, it seemed only natural to me that Highland versions of the stories involving Finn and his band of warriors might vary considerably from other known versions of the tales, especially the Irish versions. So I became really really interested in trying to understand what exactly was Macpherson’s invention, since he clearly did not invent the traditional characters of Fingal or Ossian. So what exactly did he do?

Well, he certainly collected some manuscripts of Highland poetry (I am not certain to what extent he sollicited performances of Highland poetry and/or created texts on the basis of these).

He composed Fragments of Ancient Poetry, Fingal (An Epic Poem), and Temora (An Epic Poem) between 1760 and 1763, initially at the request of and with financial support from Scottish intellectuals. These poems are loosely based on traditional tales and occasionally appear to be direct translations of Gaelic originals, but are largely poems of Macpherson’s creation. Indeed, it is wrong to call Fingal or Temora translations, though that is what Macpherson indeed called them, even when we consider how differently the act of translation was conceived in Macpherson’s day. (We only need to think of Pope’s or Chapman’s translations of Homer.) The poems (which are actually in rhythmic prose, not verse, but puport to be translations of verse originals) are explicity called epics, and, beginning with the publication of Fingal, they are attributed to an author, the blind, old warrior and poet son of Fingal, that is Ossian, whom Macpherson believed was an historical figure of the third century AD.

Macpherson never admitted to the fact that his poets were not direct transations of Gaelic originals, and even went so far as to translate both Fingal and Temora back into Gaelic word for word.

The next question is, why did he do this, and why were the poems that he created so enthusiastically received? The answer to that is the bulk of my 2006 paper, summarized here.

Macpherson’s Ossian

I can sum it all up in one word actually: Homer. Homer is so bound up in the whole Ossianic phenomenon I hardly know where to begin. But it seems at the very least that Macpherson was attempting to establish Ossian as the Homer of the Highlands in keeping with contemporary theory that postulated that epic poetry was both the highest and most primitive form of expression, and that it id in the earliest stages of society that epic is most conducive to being composed. There were these intellectual reasons for believing that Scottish epic should have existed. In addition there were patriotic reasons that I only touch on briefly in my paper but which I think are obvious if you know a little bit about Scottish history and its relationship with England at the time. And finally, as I argue in my paper, it seems that Macpherson was imagining himself in the role of Peisistratus. In doing this I don’t think Macpherson was trying to pull a fast one, believe it or not. I think that he honestly believed that Fingal and Temora once existed, in the same way that the Iliad and Odyssey existed before Peisistratus. Everything in his experience had led him to believe this must be true, and certainly the intellectuals behind these projects were supporting him in this belief, including:

His education at the University of Aberdeen

Blackwell’s Enquiry into the Life and Writings of Homer (published in 1735)

His unsuccessful attempts to publish his own poetry (epic was no longer being composed in Britain at this time, people were only interested, it seems, in “primitive” specimens of epic genius)

The great success of his Fragments of Ancient Poetry

Macpherson’s epic poetry is terrible stuff, but it was exactly what people were looking for in his day: what they expected ancient epic to be. Here are a few quotes:

Vinvela: “My love is a son of the hill. He pursues the flying deer. His gray dogs are panting around him; his bow-string sounds in the wind. Whether by fount of the rock, or by the stream of the mountain thou liest; when the rushes are nodding with the wind, and the mist is flying over thee, let me approach my love unperceived, and see him from the rock.” (Fragments of Ancient Poetry, I)

“Oscur my son came down; the mighty in battle descended. His armour rattled as thunder; and the lightning of his eyes was terrible. There, was the clashing of the swords, there, was the voice of steel. They struck and they thrust; they digged for death with their swords. But death was distant far, and delayed to come. The sun began to decline; and the cowherd thought of home. Then Oscur’s keen steel found the the heart of Ullin. He fell like a mountain-oak covered over with glistening frost: He shone like a rock on the plain. “ (Fragments of Ancient Poetry, VI)

I saw their chief, says Moran, tall as a rock of ice. His spear is like that of blasted fir. His shield like the rising moon. He sat on a rock on the shore: his dark host rolled, like clouds, around him. —Many, chief of men! I said, many are our hands of war.—Well art thou named, the Mighty Man, but many mighty men are seen from Tura’s windy walls.—He answered, like awave on a rock, who in this land appears like me? Heroes stand not in my presence: they fall to earth beneath my hand. None can meet Swaran in the fight but Fingal, king of stormy hills. (Fingal, I)

Note the simple language, the natural imagery that is repeated over and over, and the rhythmic prose. Thomas Gray wrote in a letter:

“I am gone mad about them. They are said to be translations (literal & in prose) from the Erse-tongue, done by one Macpherson, a young Clergyman in the High-lands. He means to publish a Collection he has of these Specimens of antiquity, if it be antiquity: but what plagues me is, I can not come at any certainty on that head. I was so struck, so extasié with their infinite beauty, that I writ into Scotland to make a thousand enquiries… this man is the very Demon of Poetry, or he has lighted on a treasure hid for ages.”

The invention of Ossian by James Macpherson, which was predicated on the invention of Homer by Macpherson’s eighteenth century contemporaries, came full circle when, in in the 1770s, Macpherson turned his translation efforts from Ossian to Homer himself. Once the figure of Ossian had been presented to the world and explicated within the framework of contemporary theory concerning the primitive bard, and once the inevitable comparisons began to be made between Homer and Ossian, Macpherson took it upon himself to make accessible a more accurate English text of the Homeric Iliad than had ever been available before. The scholar Hugh Blair had already pronounced Pope’s translation “of no use” for the purposes of comparing the two bards, since he had obscured Homer’s natural simplicity by imposing a meter. (Macpherson had of course translated Ossian’s verse into simple prose.) Macpherson addressed this difficulty by creating his own prose translation of the Iliad.

In the preface to his Iliad translation Macpherson makes clear what his goal is in translating Homer: “The extent of his [Macpherson’s] design has been, to give Homer as he really is: And to endeavor, as much as possible, to make him speak English, with his own dignified simplicity and energy.” [67] Elsewhere in the preface we see even more clearly what Macpherson means by “Homer as he really is”:

He seems to have trusted to the immediate resources of his genius, for the means of carrying him, through his journey. He advances, with apparent ease: Nor seems he ever to exert all his strength. He never deviates from his course, in search of ornament. In sublimity of expression and language he may be equalled: In simplicity and ease, it is difficult to ascend to his sphere. [68]

Macpherson’s Homer is once again a direct reflection of the contemporary conception of the primitive bard in his natural glory, unfettered by technique or art and sublime in his simplicity. But this conception, of which Homer was initially the defining example, is, amazingly, here being reapplied to Homer by Macpherson, precisely because Ossian has supplanted Homer as the primitive bard par excellence. Now that Ossian had been so successfully invented in Homer’s image, Homer could now be reinvented in Ossian’s.

Inventing Homer in the 21st Century

Macpherson was operating under the latest, scientific theory about the nature of man, genius, and poetry, but he was also operating under some unquestioned assumptions. Homer and Ossian as historical figures, never questioned. The search for the authentic text, the unquestioned belief in the existance of such a text, composed by Ossian himself – even though Macpherson himself had experienced the living breathing traditions first hand! (But that’s just the thing! Macpherson was on the inside of the Highland storytelling and song tradition, he believed in the myth of the culture hero – just as the South Slavic singers that Parry and Lord interviewed believed in the authorial reality of Cor Huso.) I’m curious as to whether those who see in the layers upon layers of mythological material about Homer an historical figure, whether those same people would be inclined to see historicity in Ossian.

As I note in my paper, one thing that Macpherson did not take for granted was Ossian’s literacy: his Ossian composed orally. An oral Homer was certainly not the prevailing paradigm for Macpherson’s contemporaries, though the idea was beginning to take shape over the course of the century, and in my paper I have speculated that Macpherson must have been aware of these debates. In fact, Macpherson could invent an orally composing Ossian precisely because these debates were taking place. Still, I think it is remarkable that so early in the development of the Homeric Question Macpherson was willing to take the stand that he did and find arguments to support his theory. The questions about authenticity and authorship that Macpherson’s assertion raised are as complicated as the ones that still today dominate so much of Homeric scholarship, and as I have argued, both Macpherson and Hugh Blair were concerned to address these difficult questions. They felt compelled to prove that an illiterate author was nevertheless an author, and that an authentic text composed by an authoritative author could be preserved orally. I think that if Macpherson had not been able to successfully create the authorial persona of Ossian, his work would not have been a success. The primitive genius was necessary, just as it still seems to be today for most people who read Homer.

This need for the primitive genius is the subject of my last major section of the paper, Inventing Homer in the twentieth century. There I begin by pointing out how even Parry and Lord, who are in many ways the ones responsible for models in which a genius composer need not present, operated under some of these same assumptions about authorship and genius, at least in the beginning of their work. They were looking for Homer, and so they found him in Huso (in the case of Parry) and Avdo (in the case of Lord). Parry did not have a chance really to synthesize his own fieldwork, he died before writing the magnum opus he had planned. (I for one like to think that in the course of writing that book he would have taken a new approach, he would have recognized, if he didn’t already at the time of his death, that Homer and Huso are analogous phenomena on the level of myth, not history.) Lord, the author of the so-called dictation theory, does seem to have reconsidered this idea at the end of his life, and in any case he always had an understanding of the system of oral poetry and the process of performance which he privileged above any individual composer.

When I took on this project in 2005, I was troubled that the most recent Homer to emerge, a Homer with great scholarly auctoritas behind it and the Homer that was gaining ground as the definitive one, effectively wipes out the system that Parry and Lord so painstakingly reconstructed and returns to a Macpherson like notion of the nature of authorial genius. And its here that I want to get controversial. (I hope I can, without offending too many of my colleagues...) It is certainly true that orality and literacy are not diametrically opposed states and that most cultures have a mixture of the two, and that highly literate people nevertheless rely on a variety of oral modes of communication and even authentication. This cannot be disputed. The problem is that the studies that have led to this understanding have been seized upon, I believe, in inappropriate ways by those who wish to cling to the genius composer model for Homer. Some of these studies are themselves flawed in that they originate in the very desire to show that Homer could have been literate, and they build their arguments about the nature of orality accordingly. Martin West’s Homer is an egregious example of this:

Jede [Papyrusrolle] konnte mehrere hundert Verse fassen. Um alle 15,000 Verse der Ilias aufzuschreiben (ohne den später eingefügten 10. Gesang), brauchte er eine ganze Menge Rollen. Das bedeutete eine sehr lange Arbeit. Der Dichter hat das riesige Werk offenbahr nicht in einem Zug von Anfang bis zum Ende produziert, sondern einen kürzeren Entwurf viele Jahre hindurch erweitert und ausgearbeitet; bei dieser Annahme erklären sich manche Eigentümlichkeiten des Aufbaus. Die Anzahl Rollen, die der fahrende Sänger mit sich führen musste, wuchs ständig. (“Homer durch Jahrtausende: Wie die Ilias zu uns gelangte” in Troia: Traum und Wirklichkeit, ed. J. Latacz, P. Blome, J. Luckhardt, H. Brunner, M. Korfmann, and G. Biegel, Stuttgart, 2001)

There is simply no evidence that an oral system like the one that even West has conceded once existed in ancient Greece can, within the lifetime of one man, die out and in the process produce a literate genius in full command of that system.

The only reason that West can get away with the Homer that he has invented is that so much of contemporary scholarship supports his dream of a literate, backpacking genius. Contemporary scholarship supports him because a literate Homer is the one we prefer, that’s our understanding of how great poetry is produced. In the 1760’s Homer was a primitive bard communing with nature and living in exactly the right circumstances for the production of epic. Today he is literate one, scratching out lines he’s not happy with and adding news one in the margin. Hmmm… who does this remind you of? I have little doubt that not long from now a new Homer will emerge, this time pressing the delete key and using the “track changes” function.

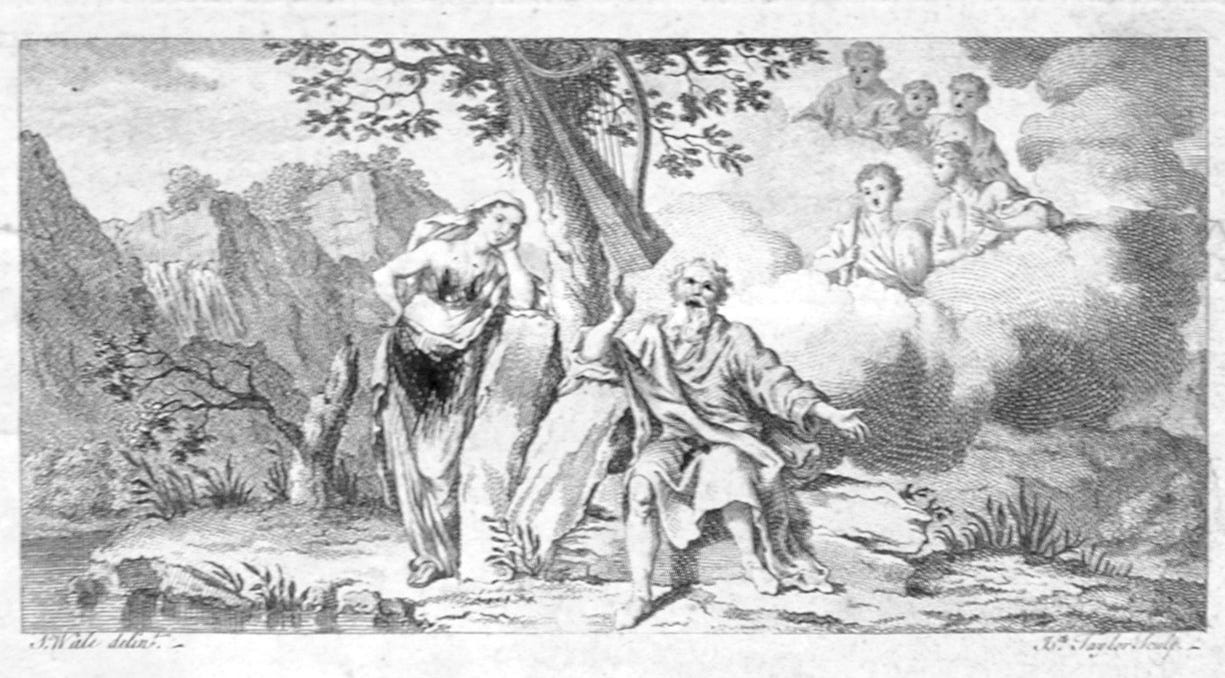

The Dream of Ossian

Ossian, slumped over his lyre asleep, dreams of the heroes of the past. Are the heroes that he dreams of depicted pale and almost as if asleep themselves because they are receding from the reach of memory, or are those heroes, as we would say, “just a dream,” a figment of the poet’s own invention? The figure of Ossian himself embodies this question, for he is both the alleged poet and at the same time hero and subject of the songs attributed to him. Did Ossian dream up his heroes, only to have that dream nearly forgotten over the course of time and then revived by James Macpherson, or was he himself dreamed up by Macpherson and Macpherson’s contemporaries?

In this paper I have tried to suggest that (1) no less than James Macpherson do we dream up Homer even as we dream of him, and that (2) no less than in the 1760’s do we continue to obsess over the question of Homer’s genius (termed, in the earliest discussions of it, “invention”). That we cannot separate the poetry from the man is signified by the existance of the many, many titles published in the last fifty years or so in English that consist of simply that magical name, Homer. Our evidence is such that however we dream up Homer it is of necessity a matter of faith and will always be rooted in current conceptions of poets and poetry. We all compose lives of Homer (even me), and each one says far more about the poetry and scholarship and the preoccupations of our own time than it does about Homer’s.

[1] F. Stafford, The Sublime Savage: James Macpherson and the Poems of Ossian (Edinburgh 1996), ix.

Great piece! Of course, Gaelic mythology has always been a strange mish-mash: https://open.substack.com/pub/brightvoid/p/we-could-be-heroes?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=9euw0